Dialogue Series, Race & Society

A Changing Kingdom: Saudi Arabia in 2030

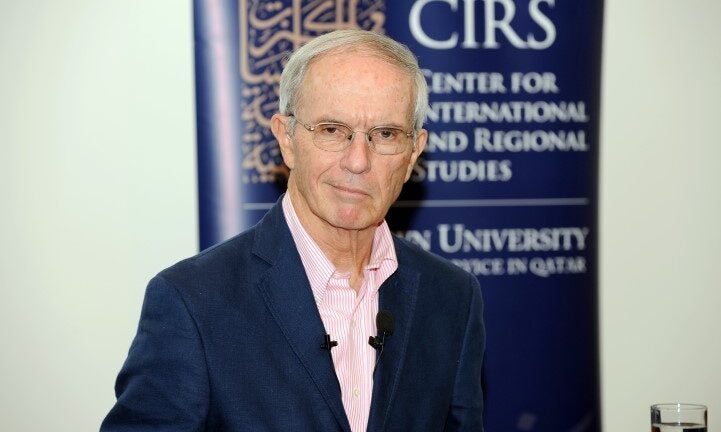

Thomas W. Lippman, former Middle East bureau chief of The Washington Post and adjunct senior fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Middle East Institute, was invited to Doha as part of the CIRS “Nuclear Question in the Middle East” working group meeting. In conjunction with the meeting, Lippman delivered a CIRS Monthly Dialogue on January 10, 2011. on the topic “A Changing Kingdom: Saudi Arabia in 2030.”

The subject of Lippman’s lecture revolved around likely future shifts in the religious, strategic, and economic principles of Saudi Arabia. There has been much literature written on the kingdom, especially since September 11, 2001, but, he argued, most of these are exaggerated accounts of radical Islam and extremism. In his new book, Saudi Arabia on the Edge: The Perilous Future of an American Ally, Lippman advocates a more sober approach to the country’s future, rather than dwelling on events of the past. Over the next two decades, Lippman argued, there will be seismic demographic and economic shifts that will affect all aspects of life in the kingdom. “Saudi Arabia has to make some very difficult and very expensive decisions in order to sustain economic growth and to maintain a basic standard of life for the population,” he said.

Listing some of the demographic and economic trends that are likely to occur, Lippman noted that “the population will grow probably by 70%, but it will grow at a slower rate than in the past.” The reason for this, he said, was because “women are collectively better educated than any previous generation and in Saudi Arabia, as anywhere in the developing world, better educate women marry later and have fewer children.” Because more women will enter the workforce, working women need a certain degree of personal mobility and will need to be able to drive legally. In the long run, he said, “Saudi Arabia cannot afford to educate all those women as it is doing, at great cost, and not recoup any of the economic output from that investment.”

Further, the current cost of living in Saudi Arabia is already extremely high and will only increase over the next few years. As such, it will become increasingly difficult to sustain large families in such an inflationary environment. Although Saudi Arabia is traditionally oil-rich, “the population has been growing faster than the GDP,” and so, Lippman argued, “the country will face the beginnings of what will be a difficult and expensive struggle to provide the population with basic necessities such as food, water, housing, and electricity.” A major consequence of the housing shortage is that the entire traditional way of life in Saudi Arabia, which is “based on living in the family compound, or in the village,” is going to change and we will see more people living in high rise apartment buildings in urban areas.

Lippman predicted that on the basis of the trends he discussed, “Saudi Arabia in twenty years, or at least by mid century, will inevitably be a more open, moderate, and educated country. It will be more like the rest of the developed world.” This is especially true since “the greatest test of the government and its ambitions was the Al Qaeda uprising” and its ultimate failure because of lack of popular support.

In conclusion, Lippman cautioned that unless there are some serious changes made, Saudi Arabia will be overwhelmed by its own demography, economy, and climate. These changes are not exactly a matter of choice; “the whole way of thinking about life and urban development is going to be inevitably transformed by the forces of demography and economics in Saudi Arabia.”

Lippman has been studying and writing about Middle East affairs for thirty five years. A frequent guest and commentator on television in the United States and in the Middle East, he is the author of five books about the Arab world, Islam and U.S. foreign policy and of several journal articles on related subjects.

Article by Suzi Mirgani, CIRS Publications Coordinator