A Team of National Representatives? Migration Histories in the Context of the FIFA World Cup

With the 2022 FIFA World Cup coming up this winter in Qatar, media debates on the migratoriness and legitimacy of foreign-born players to represent the country will most certainly emerge. During the last two editions of the FIFA World Cup (2014 and 2018), media reports have suggested that (im)migrants and national diasporas are (increasingly) contributing to the outcomes of these events. Specifically, the Qatari men’s national football team has been criticized—rather unfairly, as Ross Griffin rightly indicates—for using “nationalized”, foreign-born football players to represent the country. As footballers are appearing to be more diverse than ever, the idea of a national football team representing a unified and, arguably, homogenous nation is a reality that has long ceased to be.

Then, to what extent are representative football teams at the FIFA World Cup still—if they were ever—teams of “just” national representatives? Why would it matter if these national football teams are becoming more diverse and, as a consequence, less “nationalistic”? And, is this something new or something that truly differs from the (recent) past? I illustrate that the percentages of foreign-born players throughout the history of the (men’s) FIFA World Cup (c. 1930–2018) has remained relatively stable, between 8 and 12 percent per edition—something Gijsbert Oonk also refers to in his CIRS blog post and public talk. However, in absolute numbers, the FIFA World Cup has indeed become more migratory—with, naturally, differences between representative football teams. Besides, the countries of origin of foreign-born football players have diversified over time. These, rather visible, increases are the main drivers behind the intensification of media debates and public discussions on these issues.

In order to better understand the growth in these numbers, and to be able to correct or nuance widespread (mis)conceptions on these emotionally charged debates, the presence of foreign-born players needs historical contextualization. By making these numbers relative—that is, the number of foreign-born football players compared to the total number of footballers in the respective edition of the FIFA World Cup—the increase in the volume and diversity of foreign-born players at the FIFA World Cup, in particular during the last two decades, has not been as extraordinary as reported on in the media. Most foreign-born players in the selections of national football teams seem to relate to and reflect broader historical patterns of migration, such as colonial migrations and guest-worker migrations, and should therefore be considered as an echo and/or reversal of preceding migration flows between pairs of countries.

While the selection of foreign-born players to represent a country at the FIFA World Cup is nothing new, and will arguably only increase in the forthcoming decades, it seems to undermine the spirit and integrity of the tournament. It is the paradox that the country is represented by “nationalized”, foreign-born players who, arguably, lack a genuine connection with the country they represent, while their selection should lead to better sporting results that ultimately boost national identity. Part of these issues stem from FIFA’s regulations around the eligibility to play for representative teams in which the notion of dual nationality seems to be non-existent. These regulations seem to be at odds with the growing mobility of football players and the increasing global acceptance of dual nationality. Up until now, in the context of the FIFA World Cup, all (sporting) “nationality changes” can be perceived as expressions of a genuine link between the football player, the state, and its respective nation. Foreign-born players representing the country at the FIFA World Cup should therefore be considered as true national representatives, despite having a migration background.

Article by Gijs van Campenhout, Assistant Professor in Geography, Youth and Education at Utrecht University

Gijs van Campenhout is an Assistant Professor in Geography, Youth and Education at Utrecht University, and a member of the Sport and Nation network.

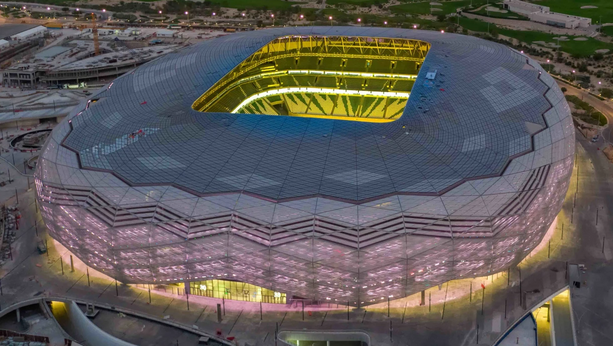

Read more about the Building a Legacy: Qatar FIFA World Cup 2022 project here.

The posts and comments on this blog are the views and opinions of the author(s). Posts and comments are the sole responsibility of the author(s). They are not approved or endorsed by the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS), Georgetown University in Qatar (GU-Q), or Georgetown University in the United States, and do not represent the views, opinions, or policies of the Center or the University.

“Who Belongs to a Country? National Representation and Identity at the FIFA World Cup 2022”

Panelists: Zahra Babar, Gijs van Campenhout, Ross Griffin, Edward J. Kolla, Peter Sprio

Moderator: Danyel Reiche

February 2, 2022

6 PM (Doha Time)