The World Cup 2022 and Qatar’s Mass Tourism Challenge: A Sustainable Future?

The State of Qatar is currently planning for the FIFA 2022 World Cup as a mass tourism sports event. But after the fans have departed, what lies ahead for Qatar’s nascent tourism industry? Historically, sports mega-events have not always provided net economic benefits for cities or nations, as argued by economist Andrew Zimbalist in his Circus Maximus: The Economic Gamble Behind Hosting the Olympics and the World Cup (Brookings Press, 2015). As cautionary tales, he points to the disastrous 1976 Montréal, Quebec Olympics (leaving the city in debt for 30 years), the cost overruns of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing, and the 2014 Sochi Winter Games.

Even though Qatar’s tourism landscape has been complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic—which caused a 73% drop in total visitor arrivals from 2019–2020, with only 500 people entering the country in April 2020—the 2022 World Cup has already provided several tangible benefits to Qatar: increased international visibility (resulting in more regional soft power), and firm target dates for much needed basic infrastructural improvements such as roads, water systems, and transport. Additionally, an unintended positive effect of hosting the tournament was a modest improvement in labor conditions in Qatar after rights groups such as Amnesty International turned their microscopes onto the abuses of the kafala system.

Tourism as a diversification strategy forms a modest part of Qatar’s “Second National Development Strategy 2018–2022.” As is well known, Qatar’s GDP continues to be dominated by hydrocarbon exports that are impacted by market forces, resulting in the revenue volatility known as the “resource curse” or “Dutch disease.” Diversification and development of a knowledge-based economy that diminishes the role of oil and gas exports have been the two key pillars of economic planning in Qatar for over two decades.

An intermediate national target of the “NDS 2018–2022” was to create “a more competitive, productive and diversified economy and a more dynamic private sector with greater contribution to the national economy,” and to “develop and coordinate priority sectors strategies (manufacturing, professional and scientific activities, logistics, financial services, tourism and ICT).” Many strides in the last decade have been made to create this diversified tourist infrastructure in Qatar, including establishing a museums sector by Qatar Museums, creating Hamad International Airport as a major transport hub, presenting Katara as a cultural space, and designating 120,00 hectares as the Al Reem Biosphere Preserve in 2007. However, Qatar’s post-2014 growth (the first year of steep declines in hydrocarbon prices) has been largely fuelled by the construction industry, a non-sustainable trajectory given the small size of the Gulf nation, and the fact that 10% of the country consists of protected reserve land.

The current Service Excellence strategic plan of Qatar Tourism (QT), the government agency tasked with the development and regulation of the tourism sector, contains not only items directly related to the World Cup (hotel and restaurant hygiene—Qatar Clean, and service worker training), but also items designed for post-tournament sustainability of the industry (enhancing tourist information, operator licensing, and developing national cultural heritage experiences).

The “Qatar National Tourism Sector Strategy 2030” launched in 2014 proposed that by 2030 tourism would: 1) constitute 5.2% of estimated total contribution to Qatar’s GDP; 2) support 7.9–10.7 million total arrivals to Qatar; and 3) generate employment for 98,000 tourist workers. Confronting this vision, however, are unfortunately several hard (environmental) limits to the number of tourist arrivals that the country can sustain. Qatar, a water scarce desert biome, remains the world’s largest per capita emitter of carbon and largest per capita consumer of fresh water. Tourists greatly exacerbate these anthropogenic environmental stressors. The realities of geography and weather in limiting large-scale tourism in desert regions are well known from case studies of Petra, Jordan, the Negev Desert, and Iran.

As I have argued in my research on desert tourism, “lack of concern for environmentally-friendly tourist behavior becomes acute in mass tourism settings [such as the World Cup], since the primary destination motivation for this consumer segment is low cost, and not necessarily an interest in natural beauty or cultural education. Also, large masses of people increase the amount of environmental stress from simple day-to-day activities—such as walking over vegetation, and they generate large amounts of non-biodegradable waste, for example plastic water bottles in hot environments.” Overtourism is now a well-recognized problem in popular destinations such as Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, Iceland, Venice, and Jordan, not only as a result of physical destruction of built heritage and natural environments, but also due to cultural change from the influx of visitors and the reduction of more stable, traditional economic activities, such as food production, as local workers move into services related to the tourist industry.

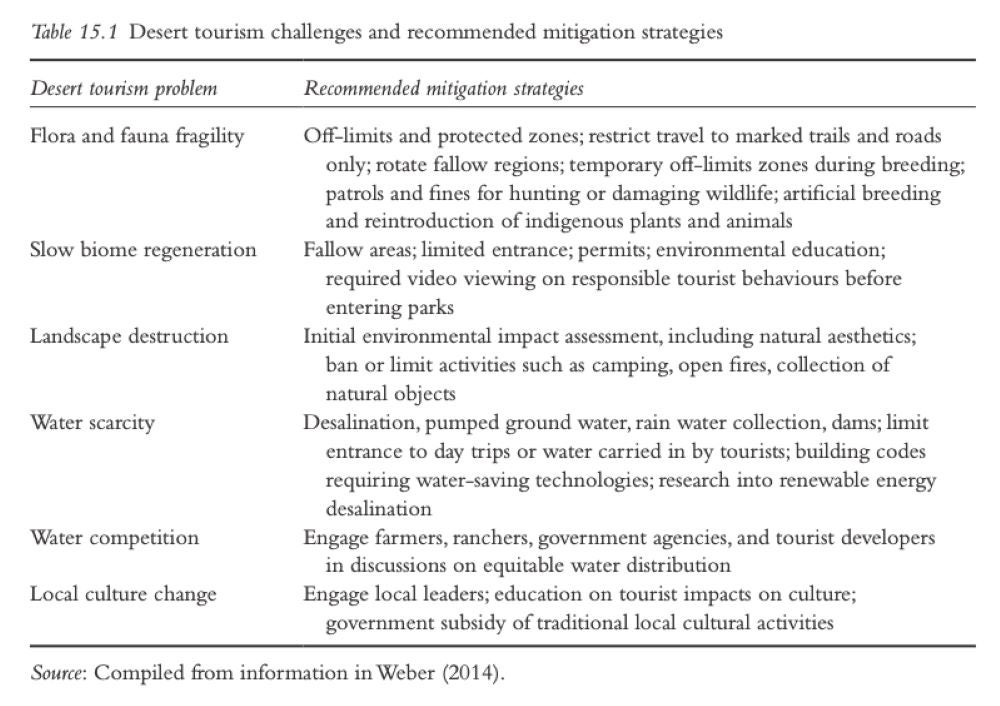

Mass tourism events, including the World Cup, have been linked to a variety of ecological and cultural sustainability issues. The World Tourism Organization of the United Nations (UNWTO) has embraced sustainable tourism as one of its core pillars for all international tourist activity, and issued the Sustainable Development of Tourism in Deserts: Guidelines for Decision Makers in 2006. Based on this work, I developed the following mitigation strategies for mass tourism in hyper-arid and arid regions, such as Qatar, UAE, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, which were published in the Routledge Handbook on Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa (Routledge 2019):

A rational and modest tourist sector development strategy for Qatar is one that does not rely on sports mega-events such as the World Cup—whose economic benefits are doubtful. This is certainly achievable, particularly if that mix includes a larger percentage of business and academic arrivals from the Meetings, Incentives, Conferences & Exhibitions (MICE) sector necessary for the further development of Qatar’s knowledge economy and creative industries. MICE events and education and training programs not only generate tourist dollars, they result in real knowledge transfer to local Qatari partners, which in turn produces the local human capacity for Qatar to produce its own knowledge (and income-generating) products such as patents, trademarked processes, copyrighted media, and technical innovation.

An economically, culturally, and environmentally sustainable tourism plan for Qatar might include: 5 million visitors per year, short-stay (3–5 days) tourism, sports tourism on a smaller scale than the World Cup or Olympics, creative and education industries tourism, niche specialty medical tourism (Aspetar sports medicine), and cultural tourism (museums, film, Bedouin homestays). For Qatar, tourism growth strategies based on shopping, economic free zones, luxury condominiums, and artificial islands will have difficulties competing with Dubai’s more mature and better advertised offerings in those areas. Many of the tourism development suggestions above have already been implemented or are in the planning stages. However, the environmental carrying capacity of Qatar must always be taken into consideration, and some of the well-studied negative consequences of overtourism, including cultural erosion, must be acknowledged.

Article by Alan S. Weber, Professor of English at Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar.

Alan S. Weber is a multi-disciplinary humanities scholar at Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar with over 170 publications in the fields of education, literature, sociology, and the history of science and medicine. He was the lead organizer of the 1st International Conference on the Medical Humanities in the Middle East in 2018. He also chaired the first International Conference on Healthcare Communication the Middle East in 2020, and in 2018 was elected as the Qatar National Representative for the International Association for Communication in Healthcare (EACH). His research on Internet Health websites in the Middle East won first prize in 2015 from the Qatar National Research Fund, and he shared with his WCMQ colleagues the 2017 Outstanding Book Award from the U.S. National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). He has published widely on tourism in the Middle East and GCC.

Read more about the Building a Legacy: Qatar FIFA World Cup 2022 project here.

The posts and comments on this blog are the views and opinions of the author(s). Posts and comments are the sole responsibility of the author(s). They are not approved or endorsed by the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS), Georgetown University in Qatar (GU-Q), or Georgetown University in the United States, and do not represent the views, opinions, or policies of the Center or the University.