The Need for Better Data on Health, Injury, and Death in Qatar

Ever since Qatar was awarded the rights to host the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup 2022, the country has come under intense global scrutiny for its treatment of migrant construction workers. Among other concerns, the question of workers’ deaths has been repeatedly raised, most recently in Amnesty International’s In the Prime of their Lives report, which asserts that Qatar has done little to investigate the numerous deaths of relatively young and healthy construction workers involved in FIFA builds.

It takes an enormous national effort to host mega sporting events such as the World Cup. Typically, such events involve thousands of migrant workers to carry out the completion of hundreds of large infrastructure projects. These efforts come under intense time pressure to meet the requirements for stadiums and other critical sport facilities as well as to support public transportation and tourism facilities.

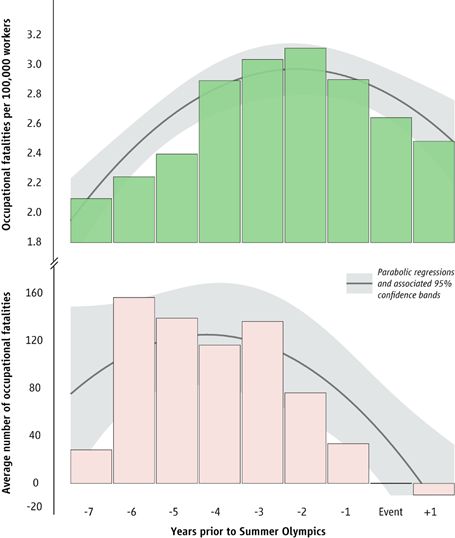

The issue of migrant construction workers’ poor health outcomes is more than just a concern for Qatar ahead of the 2022 World Cup. Data demonstrates that the migrant workers who are hired in construction projects for mega sporting events around the world experience increased health risks, injuries, and fatalities than before or after the event. In a 2021 study, we showed a substantial increase in the incidence rates of occupational fatalities in the five years before the Summer Olympic Games held between 1992 and 2016, as shown in Figure 1 below.

The bottom graph in the figure shows that occupational fatalities increase drastically in the 6-year period prior to the Olympics. To confirm that this is not driven by the increased numbers of workers being hired to build the infrastructures needed for the event, the top graph shows the occupational fatalities per 100,000 workers, confirming that deaths among laborers increase in the years before the Olympics. It is important to note that these findings are based on gross regional or national estimates that do not necessarily reflect the circumstances in the construction projects related to these mega sporting events. Data for Qatar have not been released and, therefore, it is not possible to delineate whether these findings also apply in relation to the 2022 World Cup.

Figure 1: Deaths among laborers before, during, and after the Summer Olympics in Barcelona (1992), Atlanta (1996), Sydney (2000), Athens (2004), London (2012), and Rio de Janeiro (2016).

The 2022 FIFA World Cup is an opportunity to address critical gaps in knowledge on the health and social needs of migrant construction workers in Qatar. It is vital to track the health status and health needs of these workers before arrival, during the period of migration and work in Qatar, as well as in follow up after they return home. Longitudinal assessments are necessary for understanding and addressing the complex causes of morbidity and mortality of migrant construction workers and for designing and implementing effective policy responses that address their health needs at various stages of the migration process.

As we discuss in two companion papers published recently in the British Medical Journal— “Health and Social Needs of Migrant Construction Workers for Big Sporting Events” and “Improving the Evidence on Health Inequities in Migrant Construction Workers Preparing for Big Sporting Events”—the foundation for such an endeavour, and, therefore, the first step in this process, is to improve the way that health and death data are being collected. This will allow health authorities in Qatar to better report on health needs, illnesses, injuries, and the number and causes of migrant worker deaths. Existing frameworks, nomenclature, and methodologies, such as the International Standard Classification of Occupations and the International Classification of Diseases can be adopted for this purpose, enabling much-needed cross-country comparisons.

Gathering accurate health data that cover all phases of migration—pre-migration, movement phase, arrival, and integration phase, return phase—can be a challenging task. Many migrant workers arrive in the country for a short period of time before returning home. Additionally, there are often poor links with health authorities in the migrants’ countries of origin, and many migrants are excluded from national health systems in the countries that host them. But recently developed and innovative methods of health data collection—such as the use of digital information, wearables, and smartphones—can potentially address some of these challenges. The smartphone apps tested earlier this year in large construction sites in Singapore showed very promising results, and there are many such examples worldwide. When implementing such technology-driven solutions, it is vital to ensure that collected data are used and governed safely, transparently, and ethically to ensure the protection of migrants’ rights to health privacy.

Once health, injury, and death data collection is improved, authorities in Qatar can use the data to research models of best practice, benefiting health outcomes and safety for migrant workers. This will not only drastically improve health and safety in the workplace and help Qatar meet its obligations to ensure healthy living and working conditions for its current and future migrant workforces, but will also provide critical guidance to other countries planning mega sporting events.

Article by Andreas Flouris, Leonidas Ioannou & Zahra Babar

Andreas D. Flouris, FAME Laboratory, Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Thessaly, Greece

Leonidas G. Ioannou, FAME Laboratory, Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Thessaly, Greece

Zahra R. Babar, Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS), Georgetown University in Qatar

Read more about the Building a Legacy: Qatar FIFA World Cup 2022 project here.

The posts and comments on this blog are the views and opinions of the author(s). Posts and comments are the sole responsibility of the author(s). They are not approved or endorsed by the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS), Georgetown University in Qatar (GU-Q), or Georgetown University in the United States, and do not represent the views, opinions, or policies of the Center or the University.