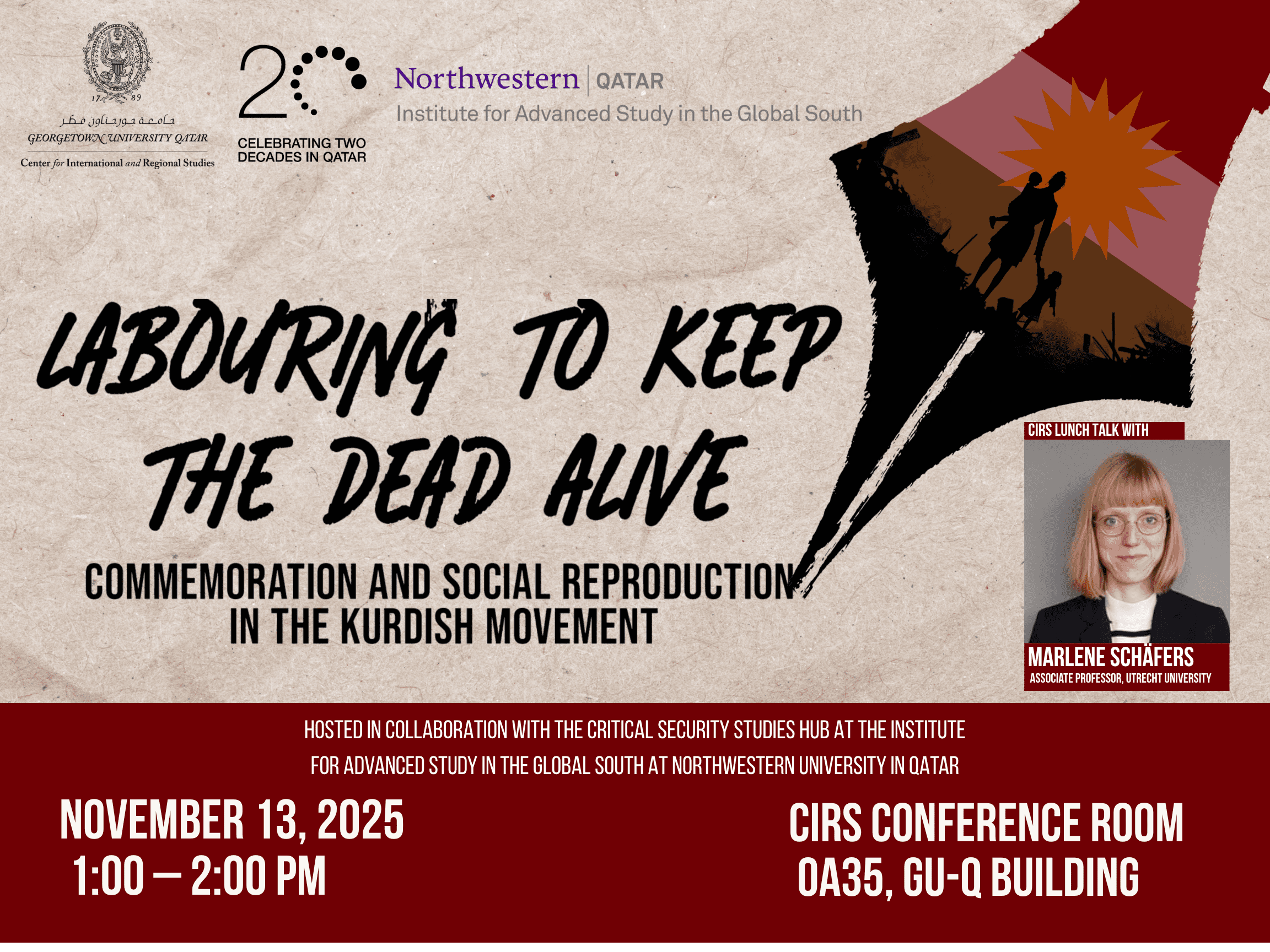

Laboring to Keep the Dead Alive: Commemoration and Social Reproduction in the Kurdish Movement

Speaker: Marlene Schäfers, Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Anthropology, Utrecht University

On November 13, CIRS hosted a lunch talk in collaboration with the Critical Security Studies Hub at the Institute for Advanced Study in the Global South at Northwestern University, titled “Labouring to Keep the Dead Alive: Commemoration and Social Reproduction in the Kurdish Movement.”

In this talk, Dr Marlene Schäfers explored how the Kurdish movement understands and mobilizes martyrdom as a form of labour that sustains the community. Drawing on examples of funerals, memorial ceremonies, social media tributes, and the production of “martyr albums,” she showed that these practices constitute a vital mode of reproductive labour, one that preserves continuity and identity when biological kinship cannot be relied upon.

What emerged clearly is that these acts of remembrance are not peripheral or decorative. They are central to how the movement reproduces itself. In contexts where traditional forms of kinship or biological reproduction cannot be relied upon, especially in guerrilla camps marked by precarity and constant threat, memory becomes a primary means of sustaining life. The speaker drew attention to the idea that narration itself becomes a reproductive act. Each story, each obituary, each ceremony extends the presence of the dead into the lives of the living. Through this narrative labour, the community cultivates what one might call descendants or extended selves, people whose identities form through their attachment to martyrs and to the struggle they represent.

A striking quote from the presentation captured this ethos: “We have learned that there are other ways of multiplying.” In other words, the reproduction of the community does not depend on producing biological offspring. Instead, it comes from producing affective ties, political commitment, and a shared sense of continuity. As one Kurdish interlocutor explained, “If you go to Kurdistan, to Rojava, and ask who Martyr Zîlan is, everyone will tell you. In this way martyrdom becomes a means of reproducing the existence of the people, and of the person herself.” Martyrs do not disappear; their memory generates new forms of political life.

The presentation also highlighted how internationalist volunteers in Rojava engage with this culture of martyrdom. For many of them, the emotional and ethical demands of this form of commemoration require a departure from liberal Western assumptions that individual life is the highest good. Instead, they are encouraged to adopt a long-term, historical view: to understand their lives as part of a continuum that includes those who fought before them and those who will continue the struggle after. This shift in orientation is both necessary and unsettling. It asks individuals to situate their grief within a broader collective horizon.

This does not mean that death becomes easy. On the contrary, participants repeatedly acknowledged that death remains bitter. One writer described rebelling against each new announcement of martyrdom, asking, “Why is there death? Are we condemned to lose our beautiful friends forever?” Even language seems insufficient. “No single word does justice to them,” another wrote. The task of writing about the dead becomes a dilemma: if one writes, the attempt feels inadequate; if one does not write, the memory risks disappearing. This tension is precisely what pushes many to take up the pen again, despite what they describe as their own lack of skill. Writing becomes a moral responsibility.

Ultimately, the speaker argued that martyrdom in the Kurdish movement is not only a political symbol. It is a mechanism of social reproduction, a way of keeping the community alive under conditions of war, displacement, and uncertainty.

Article by Maryam Daud, Administrative Assistant at CIRS

Marlene Schäfers is associate professor at the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. Her research focuses on the impact of state violence on intimate and gendered lives, voice and memory, and the politics of death and the afterlife. She specializes in the anthropology of the Kurdish regions and modern Turkey. Her first monograph, Voices that Matter: Kurdish Women at the Limits of Representation in Contemporary Turkey, was published with the University of Chicago Press in 2023 and awarded the annual Book Prize of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association in 2024.