Irony and Critique in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s The Last Supper [La última cena]

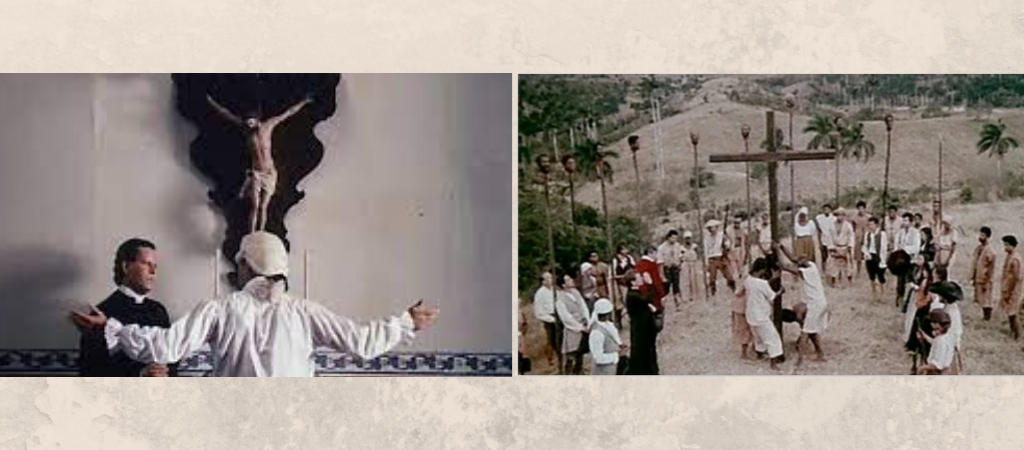

As an early beneficiary of the Culture Division of the Rebel Army (which later became the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry), Tomás Gutiérrez Alea helped to fulfill its vision of film as “an instrument of opinion and formation of individual and collective consciousness.” In the case of his film, The Last Supper (La última cena), there is no surprise in post-revolutionary Cuban cinema exposing colonialism, the Catholic Church, and slavery to withering critique, but there are some surprises about the way in which Gutiérrez Alea does so. Adapted from the historical record, his film moves beyond both costume drama and propaganda, and he himself has cited Bertolt Brecht and Sergei Eisenstein as influences. Although plainly didactic in intention and schematic in its composition, The Last Supper is far from simplistic or reductive. On the contrary, the film challenges even the most politically sympathetic viewers’ expectations, through its progression from stable to unstable ironies, and from literal contradictions between discourse and reality, to figurative contradictions.

The opening scenes, which introduce us to the plantation and its characters, invite us to appreciate the coming slave rebellion as the result of impersonal historical forces. The early dialogues between the priest and Gaspar, about witchcraft and Purgatory, lead us to think that the contradictions between Catholicism and mechanization lead to the film’s crisis. The promise of a “triple-beamed horizontal press” to speed up sugarcane processing seems like a coy secularization of the Trinity: the replacement of the slow, “vertical” hierarchy of the Church and its Holy Days with the swift horizontal efficiency of the mill itself. Likewise, we hear comments about the racial makeup of the colony, suggesting that rebellion, if and when it comes, will be the result of aggregate group conflicts, rather than individual ideas or intentions.

Similarly, Catholicism itself is ironized, with the priest’s sermon on Heaven failing to command much attention in the hellish conditions of the plantation. There are his inept commands that the men slaves wash and that the women slaves cover themselves while washing laundry, before he himself topples over in the stream in his cassock, like a slapstick botched baptism. If the overseer Don Manuel, the manager Gaspar, and the nameless priest were the only enslaving characters, Holy Week would be uneventful.

Before getting to the titular supper, we might note some stable ironies in the film’s narrative arc, for they are richly layered. The Count’s homily on the religious value of suffering is a form of sensual, doctrinal, and psychological self-indulgence; his gestures of humility turn into demonstrations of pride; his reposeful magnanimity as a “master” leads to his near loss of control; his promise of rest turns into unrest. At the end of the film, we have the slave Sebastian, named after a martyr, living rather than dying as a sign of his election by the chances of history, rather than by God.

So how does Gutiérrez Alea move beyond broad satire? The main disruptive force of the colony, and of the narrative, is not a slave, but the Count himself. His vomiting in disgust at the overseer cutting off Sebastian’s ear signals the disorder to come. Having already arranged for his Last Supper re-enactment, the Count realizes that the reality of slavery may be literally more than one can stomach, and ruin one’s appetite for Christ. But he perseveres. Crucially, the Count’s affect then becomes the film’s preoccupation: his feelings of disgust, shame, pride, sympathy, and anger. Both Don Manuel and the priest try to argue with him, to no success; his sympathies and antipathies have more authority, leading to a rebellion, which will challenge his authority.

When he suppresses the rebellion, one might see it as a betrayal of his earlier sympathetic performances. But there is no contradiction, as his sympathy was always in the service of his domination, not a check against it; both his Last Supper re-enactment and his execution of the rebel slaves are true revelations of his character. As Vincent Canby suggested in his review of The Last Supper in the New York Times, “the truth of human behavior can never be more than action observed.”

The climax of the film is the literal staging of the supper, in which the film’s diegetic form—telling a story, rather than just showing it—is compounded on itself. The original supper of Christ and the disciples would have been eaten while reclining. By setting a table, the Count is reenacting European artistic interpretations of the supper, not the event itself, and The Last Supper artfully re-enacts the re-enactment.

The Count’s supper features three parables: First, by the count, on the suffering of Saint Francis. The audience, like the slaves, is to take ironic distance from it, precisely because the Count’s sympathy with suffering is misplaced, to say the least. We are to share the slaves’ cynicism and boredom.

Then there is Briyimba’s parable of the father, son, and family selling each other out. Strikingly, he addresses the camera directly, creating another theatrical alignment between the audience and the slaves. It is a virtuosic, satirical riff on the Last Supper, scrambling its narrative of betrayal, bribery, hopelessness, and redemption, while also figuring food as the body of a forsaken, sacrificed man. As a retort to the idealistic story of St Francis, Briyimba’s parable is decidedly materialist.

Finally, there is Sebastian’s parable about the Truth wearing the head of the Lie. With the Count now unconscious, the audience is in a closer relation to the slaves, but distant from Sebastian himself, who holds a pig’s head up to his face as an illustration of the Truth–Lie hybrid. The camera looks at Sebastian obliquely, in contrast to the direct stare of Briyimba. The hybrid creature is an allegorical figure, in contrast to the quasi-human realities of the first two parables.

The three parables present different didactic uses of irony. The first parable, by the Count, is ironized by the material reality in which it is told. The second is a deployment of irony as a kind of riposte to the first. The third is a story about irony itself as a fact in the world. Whereas the first two parables seem to compete with each other directly, Sebastian’s floats above them in myth.

The fusion of truth and lies fuels the subsequent action: Did the Count promise freedom and rest, or didn’t he? Who has the machete? Who will keep their head? Sebastian escapes, but by his own telling, he will only survive through mythic transformation into something else, like a tree. In the end, the Count’s domination only grows more cruel.

At the end of that Holy Week’s scriptural shuffles, inversions, and displacements, the irreligious overseer Don Manuel is a martyr for the enslavers’ faith, in an overt analogy to Christ. The Count’s real conflict was with him all along, not with the slaves. His inefficient, naive aristocratic sentimentality was washed away by Don Manuel’s death, so that the Count himself might live anew—for another narrative of aristocratic sentimentality succumbing to the material demands of colonialism, see W. Somerset Maugham’s 1926 short story, “The Outstation.” Gutiérrez Alea leaves us with two unexpectedly transformed survivors of the rebellion and its suppression: the Count who has given up his powdered wig and ruffles and now delivers sterner homilies, and the wounded fugitive Sebastian, the only surviving disciple from the Last Supper. The cause of emancipation has more in store for both of them.

Article by Robert Carson, Assistant Professor of English, Liberal Arts Program, Texas A&M University at Qatar