Dialogue Series, Regional Studies

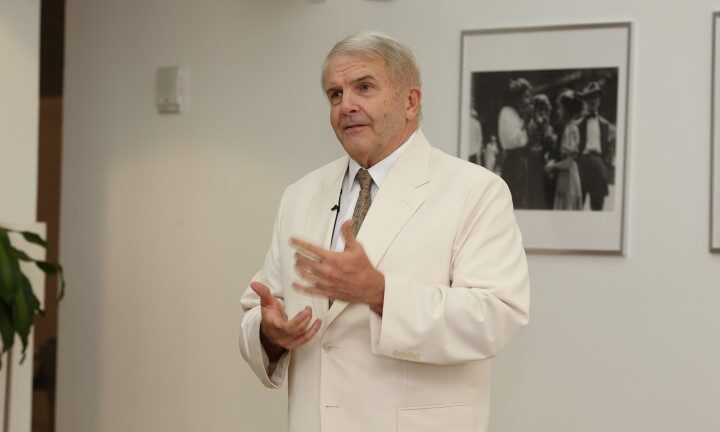

Herbert Howe on Dilemmas of Humanitarian Military Intervention in Africa

Herb Howe, Visiting Associate Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar and expert in African military conflicts, presented his lecture, “Boots on the Ground, Eyes on the Sky: Dilemmas of Military Humanitarian Intervention in Africa” on May 3, 2010 in the final CIRS Monthly Dialogue of the 2009-2010 academic year. In addition to his two decades teaching at Georgetown University, Dr. Howe spent time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nigeria and worked for both the U.S. government and as a consultant for NGO’s. He is the author of a book on African militaries entitled Ambiguous Order: Military Forces in African States.

Focusing on the tangled moral and political implications of armed peacekeeping efforts from a largely American perspective, Howe enumerated the complicating factors that must be considered when launching a humanitarian mission, including the forces of public opinion and concerns for the preservation of national sovereignty. “Boots on the ground” versus “eyes on the sky” served throughout the talk as a metaphor for the change in the prevailing ideology of peacekeeping on the continent. The former refers to an on-the-ground troops and equipment approach to assistance seen in the American efforts in Somalia in the 1990s and in various UN peacekeeping missions in Africa such as MONUC in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while the latter reflects the shift towards the training of African soldiers and sharing of satellite and intelligence capabilities in lieu of the deployment of troops to troubled regions.

Howe pointed to the issue of sovereignty as the foremost challenge in an international intervention of any kind, calling it one of the most fundamental principles of the modern nation-state.

“It is a Pandora’s Box if you start messing around with sovereignty,” he said, observing that once nations or organizations interfere in the domestic activities of states, complicated questions of the rights of governments versus responsibility to humanity arise. The violation of national sovereignty by Western powers is an especially touchy issue in Africa, where bloody battles for independence remain fresh in many minds. In situations of humanitarian intervention, outside action is justified by the idea that, according to Howe, “If you don’t act responsibly, we have the right to come in against your will and change the situation and help the people.”

The idea of a humanitarian intervention for the sake of national interest was also explored, with Howe posing the question of whether or not the spread of certain values was reason enough for an intervention.“Should this be part of our national interest,” he asked, “to safeguard these values not just for Americans and Canadians but for people around the world? Are they universal rights that people have?”

Howe also delved into the impact of domestic politics on international humanitarian interventions, pointing to the impact of negative American public opinion during the war in Vietnam and Somalia, and raised the controversial idea of allowing a war to run its own course, theorizing “war will kill a lot of people, but once that war finishes you may have a better, more durable, peace than if you try to intervene. Intervention gives people a chance to reload, it may prolong the suffering, and the post-conflict situation will be more problematic.”

To close his talk, Howe offered scenarios on what future military humanitarian interventions in Africa might look like, focusing largely on the development of an African Standby Force, consisting of soldiers from nations around the continent but aided by Western countries. Already, he pointed out, the United States has trained around 70,000 African soldiers and is offering intelligence and technological support. Because African countries have more at stake in conflicts in their own region, Howe said, there is a greater chance that their interventions will be more successful that Western-led attempts: “We’re giving them the specialized skills and they’re contributing what we don’t have—political will and commitment.”

Despite the promise that such cooperative military humanitarian interventions hold, Howe surmised that dilemmas would continue to arise, largely centered around the troubling question of whether or not Western governments would be able to ensure the responsible use of their military technology.

“Once you transfer that technology you may lose control over how it is used,” Howe said. “Is this helping the solution or leading to greater problems?

Professor Howe became interested in the topic of Africa when he served with the U.S. Peace Corps in Nigeria during the Biafra war. He subsequently freelanced in southern Africa during the liberation wars for the Philadelphia Inquirer and then taught “African Militaries” at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service for twenty years. Author of “Ambiguous Order: Military Forces in African States,” he holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

Article by Clare Malone. Malone is a Student Affairs Officer at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar.